Colonial Era Portraiture in Boston

The Nichols House Museum collection includes fascinating portraits that represent broad trends in American art and reveal the intimate relationship between artist and sitter.

Portraiture often brings to the mind oil paintings. However, an individual likeness can be captured in the two dimensional using a wide variety of media, ranging from bronze relief casting to photography. In the American Colonial period, portraiture was typically restricted to painting and engraving due to both the technology available and artistic convention.

Portraiture was the primary form of painting in the North American colonies up to the Revolution [1]. Drawing predominantly from British culture, portraits painted in the colonies sought to imitate those of nobility, clergy, and the mercantile class abroad, emphasizing individual character and status [2]. It was not until the Scottish born artist John Smibert (1688-1751) arrived in Boston in 1729 that Colonial artists had more than just a few examples to study and copy. Smibert, who had apprenticed in London under Sir Godfrey Kneller and had completed the grand tour, brought to the colonies his collection of prints, copies he had made of Old Master paintings, and his own work produced under Kneller.

By the 1720s, Boston was a mercantile city with a population of roughly 20,000. It was the most cosmopolitan city in the North American colonies and its wealthy inhabitants lived elegantly, keeping abreast of the latest London fashions and furnishing their homes accordingly. Peter Pelham (c. 1697-1751) arrived in the city in 1727, two years before Smibert. Pelham was born in London into an upper-class household and likely received a liberal arts education before becoming apprenticed to the mezzotint engraver John Simon. Simon was a leading engraver and frequently had portraits of aristocrats and dignitaries by Kneller in his studio to copy in mezzotint [3]. Thus, Pelham was exposed to the great artwork of his day. Pelham was working out of his own studio by 1720 and completed about twenty-five mezzotints, six of which were after portraits by Kneller, before emigrating to Boston [4]. Like nearly all mezzotint engravers, Pelham’s work copied portraits painted by another artist. Once established in Boston, Pelham found himself in a predicament as there was a paucity of examples from which to copy.

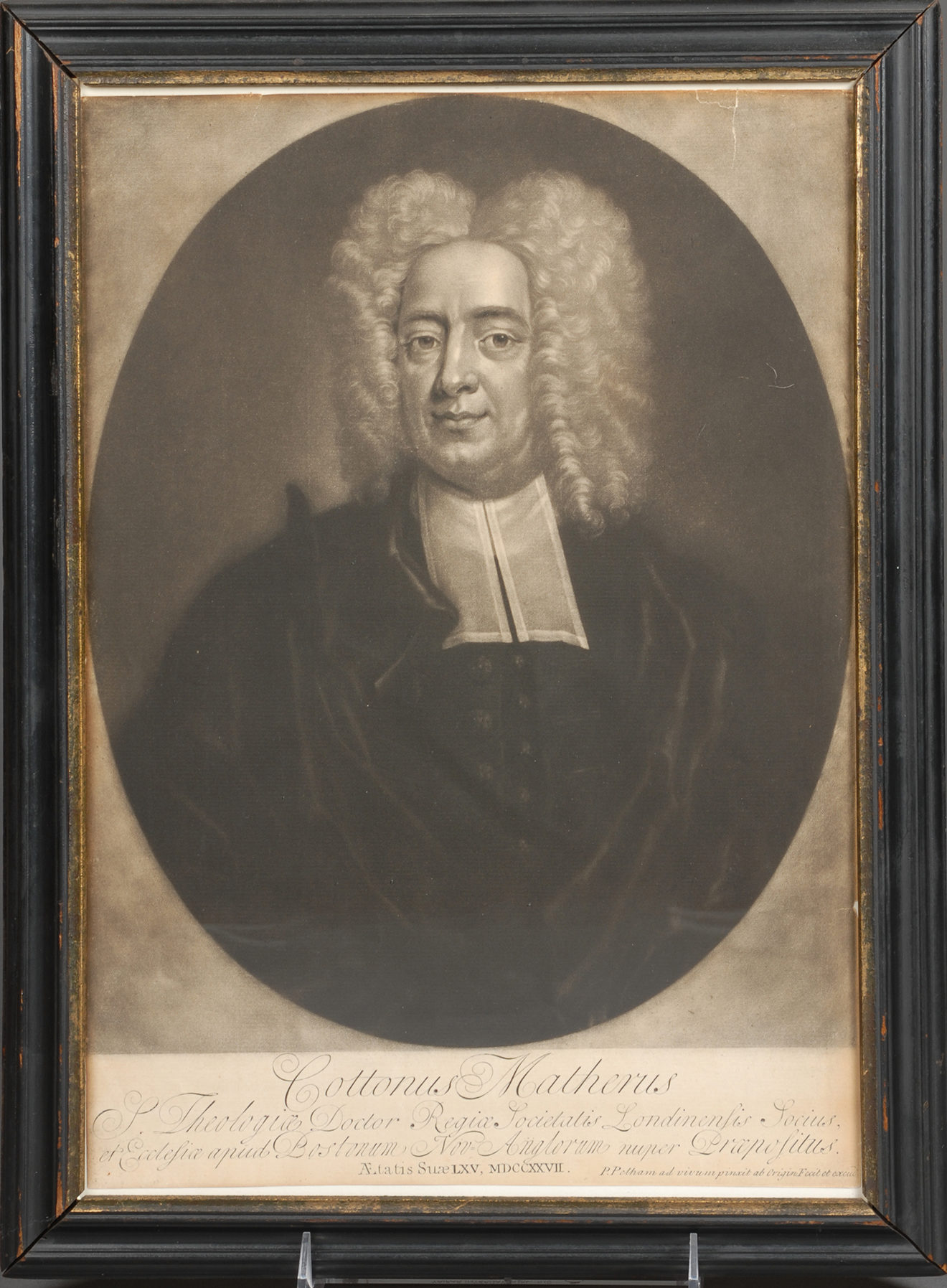

In launching his Boston career with his 1728 portrait of the venerable Cotton Mather, Pelham was forced to paint his subject himself. The painting survives in the collection of the American Antiquarian Society, however, it was the resulting mezzotint that was a great success. The mezzotint portrait in the Nichols House Museum collection (1961. 133) is either a restrike of Pelham’s engraving (a later run using the original plate) or a contemporaneous copy of the original.

Pelham’s portrait of Mather represents the high point of the artist’s career. Tones are manipulated to focus attention on the aged minister’s face while the texture of the periwig and clerical gown are carried out convincingly. Pelham captures his sitter’s haughty personality to reveal someone who is well aware of their intellectual gifts and position in society [4]. The fact that the Puritan leader wears a periwig, once a despised symbol of courtly vanity, demonstrates the burgeoning materialism and cosmopolitan nature of the colonies in the early eighteenth century [5].

Pelham brought to the colonies his expertise as a London trained mezzotint engraver; however, there was already a competent engraver active in the city at the time of his arrival. A 1729 map of Boston was engraved locally by Thomas Johnston (1708-1767), who is thought to be the subject of a portrait (1961.266) in the Nichols House Museum collection attributed to Robert Feke (c. 1707-1752). Johnston is also the great-great-great-grandfather of Rose Nichols. Like many Colonial craftsmen, Thomas Johnston practiced a number of trades in addition to engraving. He was a house painter and decorator, a japanner, a painter of coats of arms, publisher of singing-books, and an organ builder.

Robert Feke also had multiple occupational identities, which was common in the eighteenth century. Feke was born around 1707 in Oyster Bay, Long Island to a prominent Quaker family, making him the first native-born Colonial artist to achieve major recognition and success. Despite painting the elite of Boston, Newport, and Philadelphia, Feke was simply referred to as a “mariner” by his children [6].

By the 1740s, Feke had settled in Newport, Rhode Island, a city defined by maritime commerce. Newport was part of a web of Colonial American port cities with commercial connections in Africa, Europe, and the West Indies. Newport merchants were particularly active in the transatlantic slave trade, a hideousness that touched all aspects of commerce and contributed to much of the wealth and “sophistication” enjoyed by the city’s elite. The Newport of Feke’s day was what later observers would call its golden age, the decades during which it celebrated its prosperity through art and architecture, and the establishment of new institutions such as the Newport Philosophical Society and the Redwood Library. Wealthy individuals commemorated their contributions by commissioning portraits. Although Feke was only active as a painter for just over a decade, over sixty portraits attributed to him survive. Feke was in high demand not only for his talent but as a result of the “consumer revolution” taking place in the North American colonies (and because Smibert was ailing at this time). Feke’s sitters wear imported British fabrics and pose in Queen Anne chairs, and the completed portraits would decorate formal rooms in their newly built Georgian mansions.

While in Newport, Feke had access to the art collection of Dr. Thomas Moffatt, nephew of John Smibert. Both Smibert and Moffatt had come to New England as part of the Reverend George Berkely’s “Bermuda Group.” The Bermuda Group planned to establish a college for Anglican missionaries but the project failed due to a lack of parliamentary funding. Feke was probably introduced to Smibert through Moffatt and it was likely through Smibert’s recommendation that Feke received his first major commission in 1741, Isaac Royall and His Family. Feke’s group portrait of Isaac Royall, Jr. and his family was closely modeled after Smibert’s 1728 group portrait of the Bermuda Group. Isaac Royall, Jr. was one of the wealthiest men in the Massachusetts colony and a slaveowner (his 1737 mansion and slave quarters are extant as the Royall House and Slave Quarters).

Feke was most active between Smibert’s retirement in 1746 and his own death in 1752, the most likely window of time for this portrait of Thomas Johnston to have been painted. Feke settled in Boston in 1747 and during the next few years completed some of his most important portraits which capture the highest echelon of Boston mercantile society [7]. This hardly describes the portrait of Thomas Johnston in the Nichols House Museum collection.

Thomas Johnston was not wealthy but he was upwardly mobile, owning property on Brattle Street in Cambridge. It’s possible that he came into contact with Feke through his work as a framer (it’s probable that Johnston made the frame for this portrait) or through a professional network of craftsmen and clients—Johnston’s most famous apprentice was John Greenwood, who left Johnston’s studio in 1752 to pursue a career as a portrait painter in the Dutch Colony of Surinam. Greenwood modeled a group portrait of his family after Feke’s Isaac Royall and His Family and Smibert’s Bermuda Group.

Johnston’s more modest wealth is reflected in the scale of the portrait. Unlike Feke’s wealthier sitters, Johnston is not positioned against a lavish Anglo-Palladian background nor is he shown as being in possession of fashionable objects and accessories, all of which would require additional time at the easel for the artist and added costs for the client. Johnston does however wear a handsome waistcoat, likely made of imported silk. Feke took care to capture the special qualities of the fabric, with its floral design and blue and brown color scheme, as well as the fine tailoring. This materialistic demonstration, in addition to Johnston’s portly form which is carefully delineated against the background, lends status and dignity to Johnston.

Record of Rose Nichols’s acquisition of the portrait no longer exists but she is purported to have purchased it at auction in the 1930s. Research suggests that at that time the portrait was identified as Benjamin Johnston (Thomas Johnston’s son) and attributed to John Singleton Copley. Nichols, however, prominently displayed the portrait in her dining room as Thomas Johnston, her great-great-great-grandfather (Benjamin was not a direct ancestor). Colonial Revivalists proudly exhibited ancestral portraiture because it gave legitimacy to their exclusive claim on the past. In 1953, the writer and satirist John P. Marquand wrote an article on Boston for Holiday Magazine that functioned as a tongue-in-cheek eulogy of the “Proper Bostonian.” It profiled a number of aging Brahmins including Rose Nichols and her sister Margaret Nichols-Shurcliff. Rose chose to be photographed in her parlor alongside the portrait of her ancestor.

The portrait was reattributed to Feke in the 1980s. Based on when Feke was active in Boston, the sitter is more likely to be Thomas Johnston than Benjamin Johnston.

Mezzotint engraving "Cottonus Matherus" (Cotton Mather, 1663-1728) after engraving by Peter Pelham or restrike of Pelham's engraving, American, 18th century. Nichols House Museum collection, 1961.133.

Portrait possibly depicting Thomas Johnston attributed to Robert Feke (American, ca. 1707-1751), Boston, 1741-1750. Oil on canvas. Nichols House Museum collection, 1961.266.

Detail showing silk waistcoat.

Rose Nichols (far left) and the Beacon Hill Reading Group photographed for Holiday Magazine, 1953. The portrait of Thomas Johnston was hung above the parlor mantle for the purpose of the photograph.

20th-Century Portraiture

During their summers spent at the Cornish Art Colony, Rose and her sisters had their portraits painted by some of the leading artists of the day. One such example is A Reading by Thomas Dewing (1897), now in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which shows Rose (right) and her sister Marian (left) seated at a table and idly passing time. The Nichols House Museum collection features two portraits of Rose Nichols which depict her at different stages in life.

A striking portrait (T-218) of Rose Nichols by the lesser-known artist Margarita Pumpelly (Smyth) also has Cornish ties. Dating to the early 1890s, Smyth depicts Nichols as a confident and self-assured young woman.

In 1892, Arthur and Elizabeth Nichols purchased a farmhouse near the Cornish Art Colony, established in 1890 by Elizabeth’s brother-in-law, the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The Cornish Art Colony, located in and around Cornish, New Hampshire, was a summer community of creatives and wealthy patrons from Boston and New York. At Cornish, Rose kept a studio for painting and woodworking, and she shared ideas with leading artists and intellectuals.

Pumpelly was a member of the neighboring Dublin Art Colony, which art historians now view as being oppositional to the Cornish Art Colony: “the Dublin Colony was more liberal, countercultural, and stereotypically ‘bohemian’ than their more genteel neighbors” [8]. Nonetheless, Rose moved easily between the two circles, a skill that she would maintain throughout her life. Margarita was the daughter of the noted geologist Raphael Pumpelly and the family lived in Newport, Rhode Island and summered in Dublin. Rose and her sister Marian became especially close with the Pumpelly daughters and accompanied them on a months-long trip to Europe that lasted from late 1893 into 1894. It’s possible that this portrait was completed during the trip abroad.

In a 1904 diary entry, Lydia Austin Parrish, the wife of Cornish artist Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966), singled out Rose among the Nichols family as “the interesting, clever one of the lot,” and describing her as “so keen that you admire and at the same time are almost afraid of her. I can see how each year she has gained in poise, breadth and power” [9]. This wonderful description is corroborated in Pumpelly’s portrait of Rose Nichols which so clearly captures her indomitable spirit. Both artist and sitter were talented young women hampered by societal sexism and the painting captures the unique bond between the two. Perhaps Rose and Margarita, both artists, saw themselves in each other. Would a male artist have chosen to depict a young woman with an expression of such confidence?

A second portrait of Rose Nichols in the Museum collection was painted in 1929 and captures her likeness at middle-age. The artist, Polly Thayer (1904-2006), was from an upper class Back Bay family and had known Nichols since she was a girl, towed along to ladies’ luncheons and croquet games attended by her mother. Polly studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston as well as privately with Phillip Hale. Thayer began her career by painting in a more traditional fashion, observed in the portrait of Rose Nichols, however, she later experimented in modernism with great success.

Nichols took an interest in the young artist and invited Thayer to join her on a trip abroad for her research into Portuguese and Italian gardens. Polly fondly remembered Rose as “deploring what she considered the social straightjacket of the Boston debut” and introduced Thayer and her friends to a far less homogenous selection of bachelors than those at Harvard, including “the sophisticated Italian count, the voluble Dutch communist, and the seductive Turk.”

Thayer painted Rose Nichols in the summer of 1929 when Rose was visiting Thayer’s mother, Ethel, at the family’s estate, Weir River Farm, in Hingham, Massachusetts:

I asked her if she would let me paint her portrait. I found her powerful head, strong features and light-filled hair against a sallow skin deeply moving. Had Eakins known her, he would certainly have added one more to his list of masterly portraits.

Thayer described being influenced by Thomas Eakins at the time of the portrait and suggested it was modeled after Eakins’s portrait of Mrs. Gilbert Parker. Echoing Lydia Parrish’s assessment of Rose, the young artist Thayer admired Nichols’s strong presence:

Tall, gaunt, patrician, with an individual style that made no concession to changing fashion, Rose was a commanding figure in any milieu…and when I came to paint her portrait, her red velvet jacket, lace, and baroque earrings could have adorned a sitter of Goya or Holbein. There was a certain grandeur about her.

However, Nichols did not like the portrait at first, feeling it made her look too old. Not only did she initially decline to purchase it, she asked Thayer not to show it to anyone. Eventually, she agreed to it being exhibited as “Portrait of a Lady” and finally, after some time had passed, Nichols wrote Thayer asking to purchase it. It hung in the parlor of her home at 55 Mount Vernon Street, except on the one occasion when she swapped it out in favor of the Feke portrait of Thomas Johnston, her ancestor, for Marquand’s magazine profile.

Curiously, the portrait is double framed. The original frame chosen by Rose Nichols is black with a carved and gilded interior, a Colonial style that matches the frame seen on the portrait of Thomas Johnston. Nichols literally and figuratively frames herself in relationship to her ancestor and perhaps even asks to be understood in Colonial terms. In a 1956 interview with the Boston Sunday Globe, Rose said: “It was the spirit of the Puritans to try to broaden their interests toward wide horizons and that same spirit I’ve tried to keep alive in everything I’ve done.” The result is that the portraits work in tandem to shore up not only a constructed family narrative but also a regional and even a national narrative, as was the aim of the Colonial Revival. The outer gold frame was selected by the artist, Polly Thayer, in the 1980s.

In 1929, the same year she painted Nichols, Thayer won the Hallgarten Prize at the National Academy of Design for her painting Circles (1928), signaling her seriousness as a painter. Circles shows a female nude from the back, tightly painted, deliberately evoking academic tradition. However, the lively background of loosely painted circles hints at her burgeoning interest in modernism.

Thayer’s portrait of May Sarton, completed in 1936, is drastically different from her portrait of Nichols and demonstrates her departure from painting in a conventional academic style. In 1940, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston acquired Thayer’s My Childhood Trees (1938-39), one of a few modern paintings in the Museum’s collection and the first to have been painted by a Boston artist [10].

Margarita Pumpelly Smyth (American, 1873-1959), Rose Standish Nichols, ca. 1892. Oil on canvas. Nichols House Museum collection, T-218.

Polly Thayer (American, 1904-2006), Rose Standish Nichols, 1929. Oil on canvas. Nichols House Museum collection, 1961.84.

European Painting

Beginning in the late sixteenth century, it became fashionable for wealthy gentlemen to travel the great European cities as the culmination of their classical education. Known as the Grand Tour, stops were made in Paris, Rome, Florence, and Venice. Despite being in a state of economic and political decline, Venice was visited for its incredible maritime views and accompanying architecture, as well as its abundance of painting, sculpture and mural decoration.

Venice was a particularly popular tourist destination in the eighteenth century. The city hosted fairs attracting buyers to locally manufactured books, glass, and lace, as well as imported goods [11]. View painting developed in the studios of Canaletto and, a generation later, Francesco Guardi. These paintings captured romantic scenes, either real or imaginary, and often functioned as a souvenir or memento for aristocrats passing through the city. The Venetian School gave special attention to coloring or “colorito”: the blending and layering of shades of color to convey light and atmosphere.

Venice had a strong guild system in which family partnerships among artists were common. Francesco Guardi (1712–1793) trained in his family’s workshop copying the works of other artists. The style of his early views derived mainly from Canaletto, although slightly darker and softer. Guardi excelled in imaginary views, or capriccio, whereas Canaletto was known for his accuracy in depicting cityscapes. By the late eighteenth century, Guardi’s style had matured: his brushwork looser and softer, making use of an increasingly cool color palette and subtle color changes to create the effect of a shimmering atmospheric veil across the surface of smaller canvases [12]. His later work also expresses a renewed interest in chiaroscuro. While this painting (1961.168) in the Nichols House Museum collection cannot be firmly attributed to Guardi himself but rather his School (following), it represents this later period in his career. It is not an imaginary view but instead captures San Giorgio Maggiore, a Benedictine church designed by Andrea Palladio in the sixteenth century, and the surrounding seascape.

Rose Nichols purchased this painting in the 1940s from an antiques dealer on Beacon Hill. At the time of her purchase, it was attributed to Francesco Guardi. Nichols had traveled extensively throughout Italy, including Venice, when doing research for her 1928 book Italian Pleasure Gardens. Nichols’s far-reaching art historical knowledge surely motivated the purchase and she would have appreciated the painting not only for the artist but also the subject. Her 1804 home at 55 Mount Vernon Street, now the Nichols House Museum, is attributed to the Boston architect Charles Bulfinch, whose neoclassical designs were inspired by the architecture of Andrea Palladio. Bulfinch observed Palladio’s architectural designs not only in print but also as a Grand Tourist from 1785 until 1788—around the time this view was painted.

San Giorgio Maggiore attributed to the School of Francesco Guardi, mid to late 18th century. Oil on canvas. Nichols House Museum collection, 1961.168.

Detail showing architecture of San Giorgio Maggiore designed by Andrea Palladio.

Japanese Woodblock Prints

Distinct in the Nichols House Museum collection are three Japanese woodblock prints in the ukiyo-e (pictures from everyday life) style by the Edo masters Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825) and Hiroshige (1797-1858).

In 1765, new technology allowed single-sheet prints to be produced in an array of colors [13]. Previously, printmakers worked in monochrome, painted in colors by hand, or printed using only a few colors. Great print masters such as Toyokuni and Hiroshige used polychrome to capture the splendor of kabuki theater as well as romantic landscapes and vistas. These prints were hugely popular among wealthy inhabitants of the city of Edo (renamed Tokyo in 1868).

Although fame was enjoyed by the artists, woodblock printing required the collaboration of multiple craftsmen and experts: the artist, the engraver, the printer, and the publisher. First designed by the artist on paper, the image was then transferred to thinner, semi-transparent paper for the engraver to trace and carve in the negative into a block of wood. The ink was then applied to the raised relief followed by a piece of paper laid over the inked woodblock. Finally, a round pad was rubbed over the back to make the print. Polychrome prints required that separate carved blocks for each color be carefully aligned. Reproductions were made until the woodblocks became too worn.

Toyokuni was celebrated for his dynamic prints of kabuki actors. This example (1961.487) by Toyokuni in the Museum’s collection features an unknown kabuki actor occupying the space of the entire print. The actor strikes an active pose, looking over his shoulder while grasping one of the two swords that protrude from his obi. Toyokuni’s major achievement was his Yakusha butai-no-sugatae (Portraits of Actors in Their Various Roles), a series of large polychrome prints created between 1794 and 1796. These are full-length portraits, often of single actors, against plain backgrounds. Although not of that series, this print dates to around that time.

It’s thought that Hiroshige applied to study under Toyokuni but was not accepted. Hiroshige instead entered the school of the ukiyo-e master Utagawa Toyohiro. Although less popular than Toyokuni, Toyohiro’s more refined approach allowed Hiroshige to develop his own sophisticated style, which found full expression in the new genre of the landscape print. Hiroshige’s first landscape period, from 1830 to about 1844, was the high point of his career, during which he completed Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. The success of this series was immediate and propelled Hiroshige to fame. His second landscape period, lasting from about 1844 until his death in 1858, saw something of a decline in the quality of his work due to overproduction stemming from his popularity. It has been estimated that Hiroshige created more than 5,000 prints and that as many as 10,000 copies were made from some of his woodblocks.

The two prints in the Nichols House Museum collection by Hiroshige date toward the end of his career. The triptych, Cherry Blossoms on the Bank of the Sumida River (1961.474), completed sometime between 1847 and 1852, shows well-dressed women (possibly geisha) enjoying cherry blossom season along the Sumida River, possibly in Asukayama. The mountain in the far right corner is likely Mount Tsukuba. The single print, Scene of Yedo (1961.463), shows a well-dressed group trailed by two figures. By the eighteenth-century, Edo (renamed Tokyo in 1868) was the largest city in the world with a population of more than one million people. Many of Hiroshige’s prints depict modern urban life.

In 1854 Japan opened itself to the Western world after 200 years of isolation. Japanese art and culture became extremely popular in France, Europe, and the United States and this fascination lasted into the twentieth century. Ukiyo-e prints greatly influenced the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, who appreciated them for their use of color, perspective and balance, and depiction of the modern world.

These prints were gifted to Rose Nichols by an R. Kita, whose identity is unknown.

Laura Cunningham

Curator of Collections and Education

May 2020

[1] Bostwick Davis, Eliot, and Erica E. Hirshler, Carol Troyen, Karen E. Quinn, Janet L. Comey, and Ellen E. Roberts. “Colonial and Federal America: The Rise of the New Nation.” In MFA Highlights: American Painting. MFA Publications: 2003.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Craven, Wayne. Colonial American Portraiture. Cambridge University Press: 1986.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Anishanslin, Zara. Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the Atlantic World. Yale University: 2016.

[7] Bostwick Davis, Eliot, and Erica E. Hirshler, Carol Troyen, Karen E. Quinn, Janet L. Comey, and Ellen E. Roberts. “Colonial and Federal America: The Rise of the New Nation.” In MFA Highlights: American Painting. MFA Publications: 2003.

[8] Dimock, Maggie. Life at Mastlands: Rose Standish Nichols and the Cornish Art Colony. Nichols House Museum: 2014.

[9] Lydia Parrish Diary, January-June 1904. Box 8, Folder 32. Maxfield Parrish Papers, ML-62. Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College.

[10] Hirshler, Erica E. A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston, 1870-1940. MFA Publications: 2001.

[11] Baetjer, Katharine. “Venice in the Eighteenth Century.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, October 2013. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/venc/hd_venc.htm.

[12]“Francesco Guardi.” National Gallery of Art. Accessed June 13, 2020. https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1363.html.

[13] “Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, October 2003. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ukiy/hd_ukiy.htm.

Utagawa Toyokuni, Kabuki actor, Japan, late 18th to early 19th century. Woodblock print. Nichols House Museum collection, 1961.487.

Hiroshige, Cherry Blossoms on the Bank of the Sumida River, Japan, ca. 1847-52. Woodblock print. Nichols House Museum collection, 1961.474.

Hiroshige, Scene of Yedo, Japan, ca. 1844-58. Woodblock print. Nichols House Museum collection, 1961.463.